Below is my e-portfolio for EDCI 339:

———————————————————————————————————————–

Revised Blog

Attached links to individual topic blogs:

Here is a link to a google doc where you can see my edits. I edited my blog post and added two new outside sources and an infographic!

Enjoy the final draft blog below!

How can you ensure equitable access to authentic, meaningful & relevant learning environments for all learners in K-12 open and distributed learning contexts? What did you already know, what do you know now based on the course readings and activities, what do you hope to learn?

When considering equitability in open and distributed learning environments, one has to examine the whole learner- homelife, access to technology, past education experience, exceptionalities, and cultural identity.

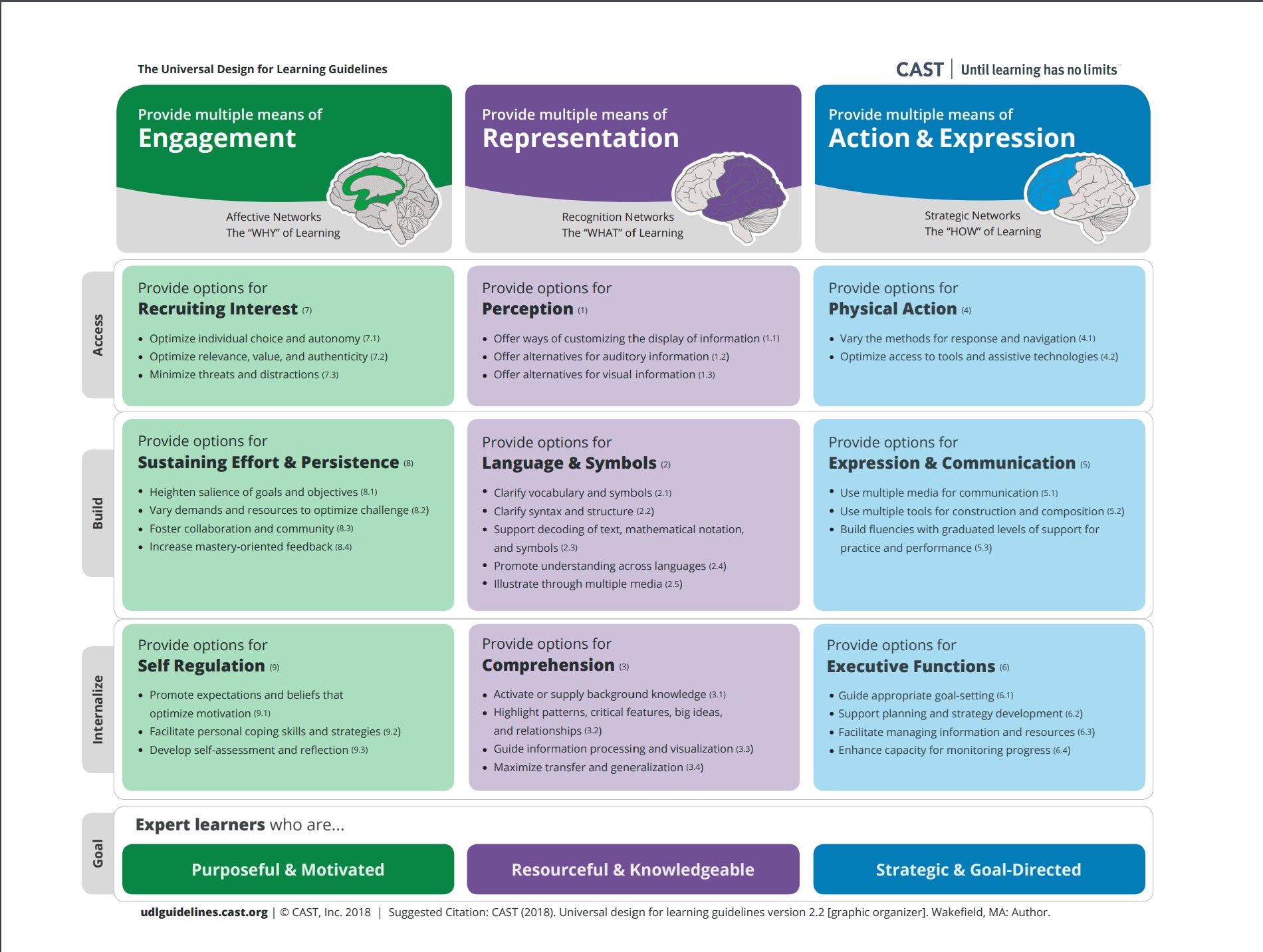

One approach that many educators are now using, to ensure equitability in the classroom, is the Universal Design for Learning, defined by Basham et al. (2018) as “educational systems that offer multiple ways of engaging students, representing information, and demonstrations of mastery” (2018, p.477). UDL uses a learner-centred approach, which inherently makes the teacher ensure equitable access for every student. Terence Brady in his TED talk “Universal Design for Learning—A Paradigm for Maximum Inclusion” agrees with this statement, saying that UDL at its core is inclusive only because it is student-centred. He continues stating that we “must view difference as an everyday occurrence in the educational process and celebrate it.” By using UDL we are able to create accessible and equitable learning.

UDL consists of three main principles and 3 more subcategories (total of 9) as seen in this chart. These principles are integrated into the lesson planning process to foster an inclusive design style.

Link to the interactive version

Link to the interactive version

Adding a UDL approach to an online environment can be more difficult than a F2F class but it makes open and distributed learning an option for students with exceptionalities. In a fully online environment, UDL was proven to “[enhance] the learner perception of their own efforts and increase persistence in large-scale online course completion” (Basham et al., 2018, p.489). Furthermore, in an online-blended-environment, UDL was proven to “increase learner satisfaction and learning outcomes” (Basham et al., 2018, p.489). Many federal education initiatives have begun to adopt and endorse the theory because of its research base (Basham et al., 2018, p.480)

The implementation of UDL in both brick-and-mortar schools and online school systems has enabled teachers to begin the class expecting and normalizing student learning diversity which enables all to have an equal chance to succeed and grow.

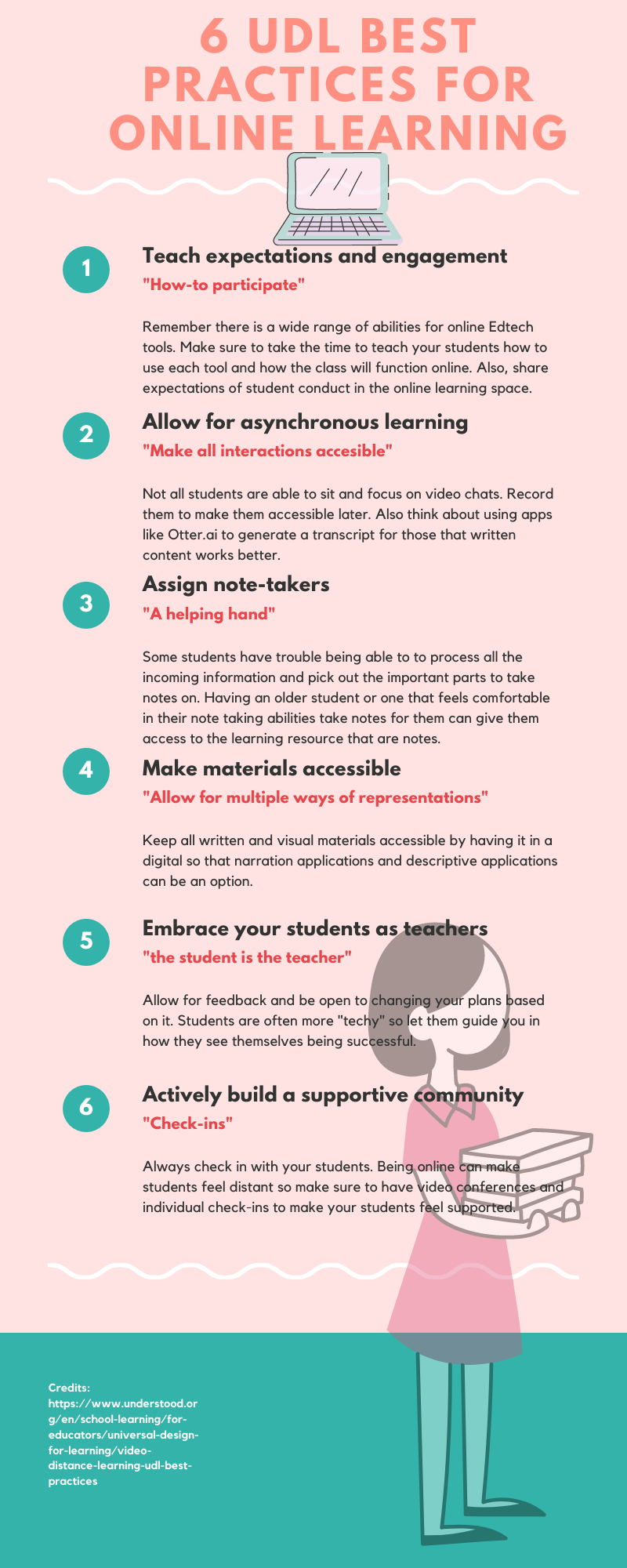

Here is a link to an article about how to use UDL in an online environment. The website also has a whole series on “Reaching and Teaching all students with UDL”. I have also created an Infographic using Canva to highlight the main ideas!

Another consideration when creating equitable access to an open and distributed learning environment would be a student’s cultural background. We must have representation and resources to make all students feel valued. This is especially important for Canada’s Indigenous youth because part of the reconciliation efforts is the curriculum’s calls for Indigenous education to be represented in public schooling. Here is a graphic of the First Peoples Principles of Learning that educators across BC reference to help integrate Indigenous principles into their classroom and lesson plans.

PUB-LFP-POSTER-Principles-of-Learning-First-Peoples-poster-11×17

When considering the cultural background of students in an online environment, it is important to make sure each person feels seen, valued, represented, and supported. There are 8 design principles outlined by Kral and Schwab (2012) that can help teachers do just this. These principles are:

1: A space young people control

2: A space for hanging out and mucking around

3: A space where learners learn

4: A space to grow into new roles and responsibilities

5: A Space to Practice oral and written language

6: A space to express self and cultural identity through multimodal forms

7: A space to develop and engage in enterprise

8: A space to engage with the world

(Kral and Schwab, 2012, p. 58-90)

Beyond the classroom (online or in-person), it is also important to have Indigenous learning centres that offer resources to areas that may have low access to technology, which in turn allows Indigenous youth to represent themselves and preserve their culture and language in new and innovative ways (Kral and Schwab, 2012).

Creating equitable access requires dedication and forethought. As stated in Neil Selwyn in his blog titled “Online learning: Rethinking teachers’ ‘digital competence’ in light of COVID-19”, teachers are being faced more now than ever with the challenges of creating an online environment due to COVID-19. It is important, now and always, to look to the experts who have dedicated their careers to making an online environment equitable for all their students. In doing so, we can build an online learning community that is open to all learners, and those learners will feel supported and able to succeed.

Resources:

Basham, J.D., Blackorby, J., Stahl, S. & Zhang, L. (2018) Universal Design for Learning Because Students are (the) Variable. In R. Ferdig & K. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (pp. 477-507). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University ETC Press.

CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2 [graphic organizer]. Wakefield, MA: Author.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC). (n.d.). Retrieved July 20, 2020, from http://www.fnesc.ca/

Kral, I. & Schwab, R.G. (2012). Chapter 4: Design Principles for Indigenous Learning Spaces. Safe Learning Spaces. Youth, Literacy and New Media in Remote Indigenous Australia. ANU Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/LS.08.2012 Retrieved from: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p197731/pdf/ch041.pdf

Selwyn. N. (2020). Online learning: Rethinking teachers’ ‘digital competence’ in light of COVID-19.[Weblog]. Retrieved from: https://lens.monash.edu/@education/2020/04/30/1380217/online-learning-rethinking-teachers-digital-competence-in-light-of-covid-19

Schlichtmann, G. R. (2020, May 27). Distance Learning: 6 UDL Best Practices for Online Learning. UDL Best Practices for Distance Learning. https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/universal-design-for-learning/video-distance-learning-udl-best-practices.

Tedx Talks. (2017, February 10). Universal Design for Learning—A Paradigm for Maximum Inclusion | Terence Brady | TEDxWestFurongRoad [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRZWjCaXtQo

————————————————————————————————————————

Optional activities

included within each artifact:

- Connections to course outcomes

- Connection to course content

- Connection to outside sources

- The reason for choosing that activity

- Other miscellaneous connections and thoughts

————————————————————————————————————————

Optional activity 1: Webinar with Dr. Bard Brown

Here is an article link to further define Alan Mclean’s 3 A’s and one to define Circle of Courage as I talked about in my audio recording.

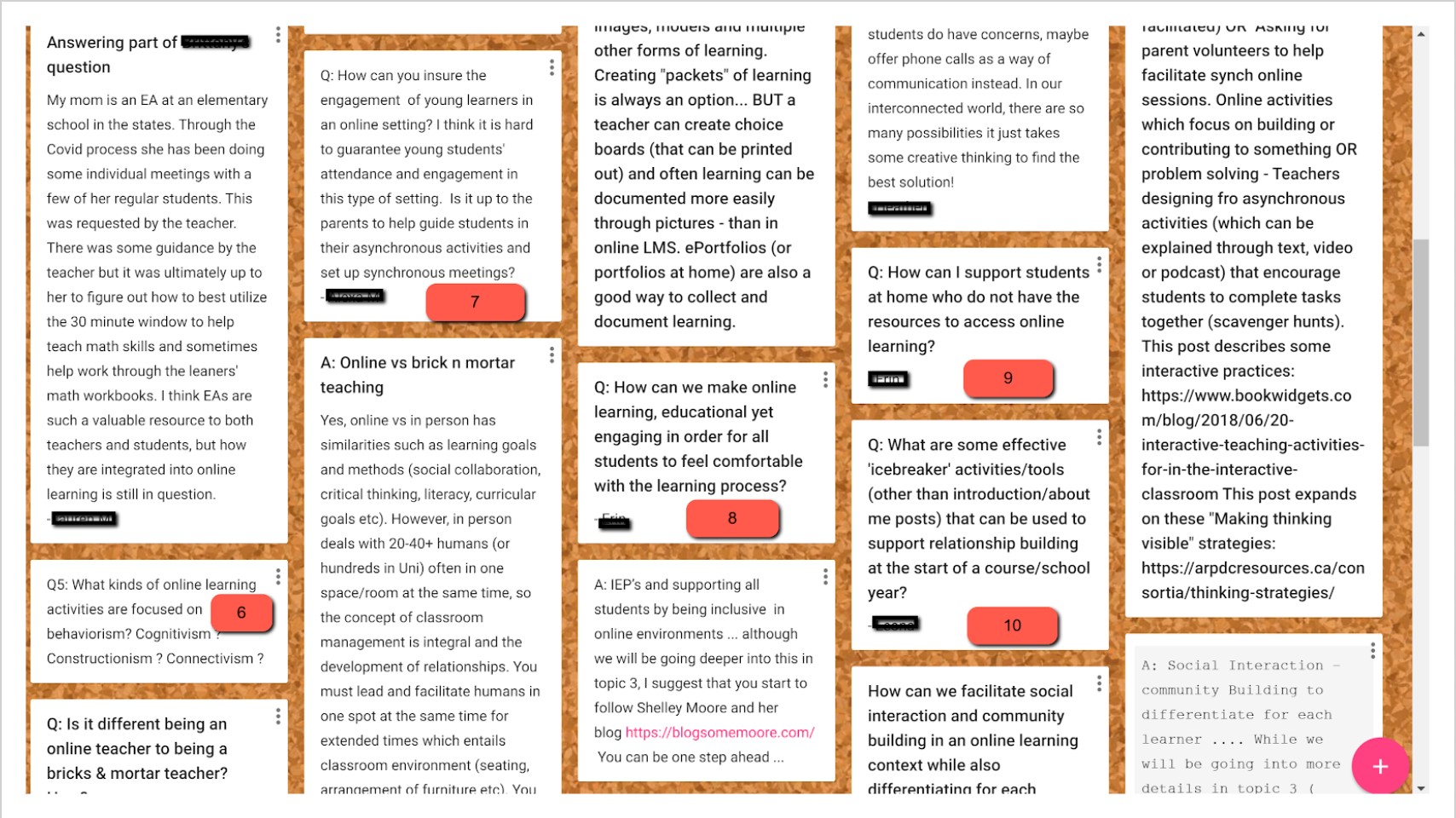

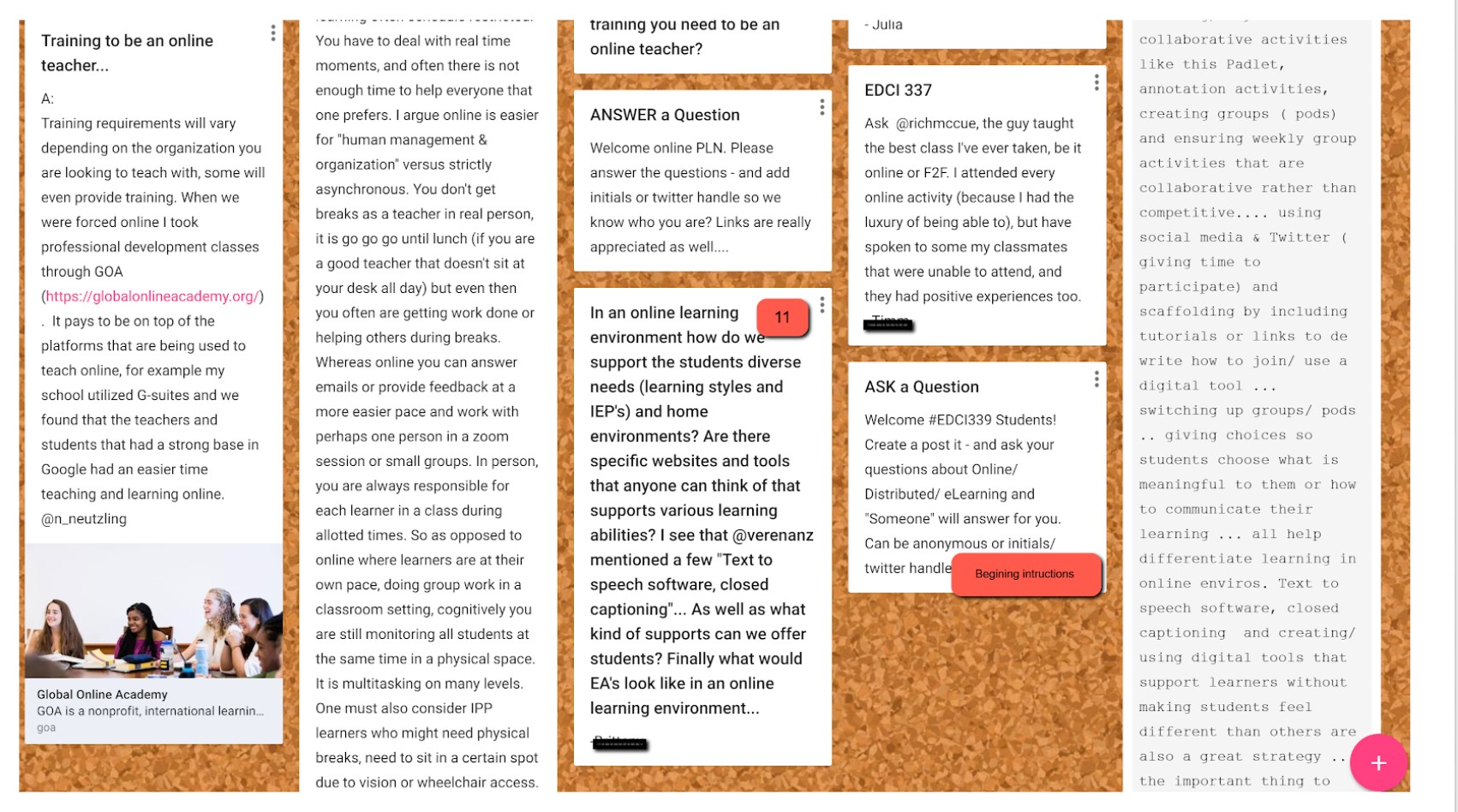

Optional activity 2: Padlet

Here is a Google Slides to describe my Padlet experience.

My Padlet question was #7.

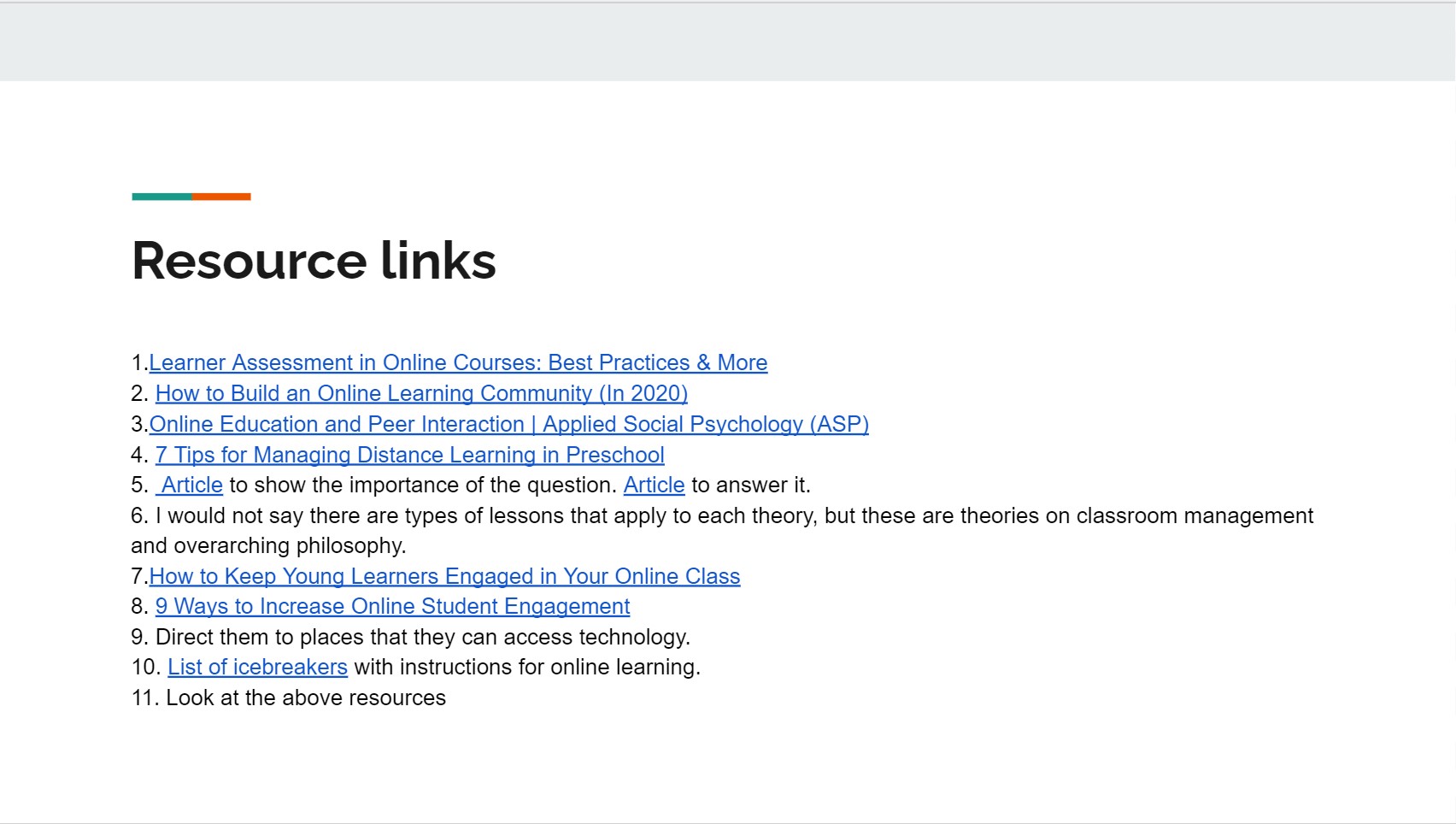

Link to articles to answer the Padlet questions

Optional activity 3: Slack Conversation

link to a transcript of the video (I strayed from the script a little bit but these are the main points that I spoke about in the video!)

Optional activity 4: Live Twitter Conversation

Link to transcript version.

Here is a link to 15 ways to use Twitter in education. I found it helped me visualize how it can be used in education!

Citations:

Circle of Courage Images–Source: Used with permission. Artist: George Blue Bird. The Circle of Courage is a Trademark of Circle of Courage, Inc. For more information, see Web site: www.reclaiming.com or e mail: courage@reclaiming.com. Principles of the Circle of Courage–Source: Used with permission. From Reclaiming Youth at Risk: Our Hope for the Future by Larry Brendtro, Martin Brokenleg, and Steve Van Bockern (pgs. 137-138). Copyright 1990 and 2002 by Solution Tree (formerly National Educational Service), 304 West Kirkwood Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47404, 800-733-6786, www.solution-tree.com.

Source: Reclaiming Youth Network. “The Circle of Courage Philosophy.” 2007. (13 July 2007). Reproduced with permission.

Ways to Increase Online Student Engagement. 9 Ways to Increase Online Student Engagement | WBT Systems. https://www.wbtsystems.com/learning-hub/blogs/9-ways-to-increase-online-student-engagement.

Burdette, P. J., Greer, D., & Woods, K. L. (2013). K-12 online learning and students with disabilities: Perspectives from state special education directors. Online Learning, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v17i3.327

Deschaine, M. E. (2020, April 20). Supporting Students with Disabilities in K-12 Online and Blended Learning. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/supporting-students-with-disabilities-in-k-12-online-and-blended-learning/.

Dr Valeria (Lo Iacono) Symonds on June 14, Dr Valeria (Lo Iacono) Symonds on July 15, & *, N. (2020, July 15). 21 Free fun Icebreakers for Online Teaching and virtual remote teams: Symonds Training. Symonds Research Training Course Materials. https://symondsresearch.com/icebreakers-for-online-teaching/.

The motivated school. Pivotal Education. https://pivotaleducation.com/hidden-trainer-area/training-online-resources/the-motivated-school/.

Moore, S., & Hodges, C. B. (2020, March 11). Inside Higher Ed. Practical advice for instructors faced with an abrupt move to online teaching (opinion). https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/03/11/practical-advice-instructors-faced-abrupt-move-online-teaching-opinion.

Muskin, M. (2020, April 29). 7 Tips for Managing Distance Learning in Preschool. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/7-tips-managing-distance-learning-preschool.

Norman, S. (2018, March 12). 15 Ways To Use Twitter In Education (For Students And Teachers Alike). https://elearningindustry.com/15-ways-twitter-in-education-students-teachers.

N., J. (2018, December 5). How to Keep Young Learners Engaged in Your Online Class. TwoSigmas. https://twosigmas.com/blog/how-to-keep-young-learners-engaged-in-your-online-class/.

Papadopoulou, A. (2019, December 20). Learner Assessment in Online Courses: Best Practices & More. Learnworlds. https://www.learnworlds.com/learner-assessment-best-practices-course-design/.

Papadopoulou, A. (2020, April 28). How to Build an Online Learning Community (In 2020). Learnworlds. https://www.learnworlds.com/build-online-learning-community/.

PSYCH 424 blog. Applied Social Psychology ASP RSS. (2017, October 30). https://sites.psu.edu/aspsy/2017/10/30/online-education-and-peer-interaction/

Roberts, V. , Blomgren, C. Ishmael, K. & Graham, L. (2018) Open Educational Practices in K-12 Online and Blended Learning Environments. In R. Ferdig & K.Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (pp. 527–544). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University ETC Press..

Selwyn. N. (2020). Online learning: Rethinking teachers’ ‘digital competence’ in light of COVID-19.[Weblog]. Retrieved from: https://lens.monash.edu/@education/2020/04/30/1380217/online-learning-rethinking-teachers-digital-competence-in-light-of-covid-19

Schlichtmann, G. R. (2020, May 27). Distance Learning: 6 UDL Best Practices for Online Learning. UDL Best Practices for Distance Learning. https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/universal-design-for-learning/video-distance-learning-udl-best-practices.

Tedx Talks. (2017, February 10). Universal Design for Learning—A Paradigm for Maximum Inclusion | Terence Brady | TEDxWestFurongRoad [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRZWjCaXtQo

Verenanz. (2020, July 23). Questions for Online & Open K-12 Teachers. https://padlet.com/verenanz/5na90f0mkywgdcmh.

through Project-Based Learning (PjBL) and an emphasis on global-citizenship (PenPal Schools, 2020). It is used by schools in over 150 countries and allows students (8 and older) to engage with other learners in “thoughtfully designed, collaborative projects” (Wilson, 2018). These projects are offered in many of the core subjects along with others such as Environmentalism, Social Justice, and Current Events (PenPal Schools, 2020). They involve “self-guided, differentiated and mixed media” lessons based on a chosen topic (Wilson, 2018). In the lessons, learners read and analyze texts, watch videos, share ideas in a forum space, and collaborate all while “[building] empathy, curiosity, and respect” (PenPal Schools, 2020). The team at PenPal Schools curates each lesson to align with different international educational standards in the areas of “reading, writing, digital citizenship, and social-emotional skills” (PenPal Schools, 2020). Teachers sign up for PenPal Schools and receive their first topic for free (more topics can be obtained through referrals, fees, or scholarships) (PenPal Schools, 2020). In regards to safety, students can only join through a teacher invitation and the only personal information required is the student’s first names, last initials, and country. Every post is moderated and student safety is the application’s number one concern. Click

through Project-Based Learning (PjBL) and an emphasis on global-citizenship (PenPal Schools, 2020). It is used by schools in over 150 countries and allows students (8 and older) to engage with other learners in “thoughtfully designed, collaborative projects” (Wilson, 2018). These projects are offered in many of the core subjects along with others such as Environmentalism, Social Justice, and Current Events (PenPal Schools, 2020). They involve “self-guided, differentiated and mixed media” lessons based on a chosen topic (Wilson, 2018). In the lessons, learners read and analyze texts, watch videos, share ideas in a forum space, and collaborate all while “[building] empathy, curiosity, and respect” (PenPal Schools, 2020). The team at PenPal Schools curates each lesson to align with different international educational standards in the areas of “reading, writing, digital citizenship, and social-emotional skills” (PenPal Schools, 2020). Teachers sign up for PenPal Schools and receive their first topic for free (more topics can be obtained through referrals, fees, or scholarships) (PenPal Schools, 2020). In regards to safety, students can only join through a teacher invitation and the only personal information required is the student’s first names, last initials, and country. Every post is moderated and student safety is the application’s number one concern. Click  ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019).

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019). Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom.

Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom. Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humour, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humour, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals. Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).

Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356). evaluation we will be

evaluation we will be

I think that videos are often the most effective and engaging form of multimedia for young learners. I also understand that videos can also be a part of homework or pre-class work that is left undone. The Google training suggested that a Google form could be a good way to check for understanding once the video is watched. I see H5P as a potentially more effective way to check for understanding because the important ideas are emphasized (signalling principle) while the information is being absorbed. This protects against becoming disengaged while watching the video and then failing a quiz. Indeed, a student will watch with anticipation of a quiz, making them more engaged, and then when a question or annotation is included, it will clue them in to what points are important. By having an application such as H5P, I can ensure that my students are not only watching the videos but also hitting the learning outcomes I was intending.

I think that videos are often the most effective and engaging form of multimedia for young learners. I also understand that videos can also be a part of homework or pre-class work that is left undone. The Google training suggested that a Google form could be a good way to check for understanding once the video is watched. I see H5P as a potentially more effective way to check for understanding because the important ideas are emphasized (signalling principle) while the information is being absorbed. This protects against becoming disengaged while watching the video and then failing a quiz. Indeed, a student will watch with anticipation of a quiz, making them more engaged, and then when a question or annotation is included, it will clue them in to what points are important. By having an application such as H5P, I can ensure that my students are not only watching the videos but also hitting the learning outcomes I was intending.  multimedia experience for your students. In an online school setting, like what we see in schools right now, I could see creating tutorials or vlogs for my students and having annotations, quizzes, and questions added on top to make my content more engaging. This would be a good way to have an asynchronous style of learning, while still having an element of guided discovery like Mayer outlines. I also love that I can utilize all of the amazing educational resources on Youtube as well. There is so much in the world of video creation and animation that I simply don’t have the skill set to accomplish, so having a way to use others professionally developed content, but adapt it to my learning style and learning outcomes is incredibly useful.

multimedia experience for your students. In an online school setting, like what we see in schools right now, I could see creating tutorials or vlogs for my students and having annotations, quizzes, and questions added on top to make my content more engaging. This would be a good way to have an asynchronous style of learning, while still having an element of guided discovery like Mayer outlines. I also love that I can utilize all of the amazing educational resources on Youtube as well. There is so much in the world of video creation and animation that I simply don’t have the skill set to accomplish, so having a way to use others professionally developed content, but adapt it to my learning style and learning outcomes is incredibly useful.